This article is the third part of the Healthy Forests series. Read Part 1: Along the Yampa River, here and Part 2: Mountain Trees, here.

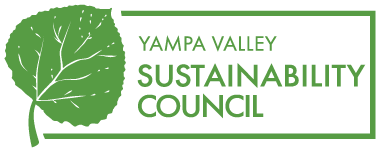

The Standing Dead Triptych: Wildfire, The Standing Dead and Rebirth, paintings by Silas Axtell.

Living surrounded by forests in Routt County, we are also living with the risk of wildfire. The issues around forest fires are complicated, evolving, and include benefits as well as damages.

In the early 1900s there were large and destructive wildfires in the Western United States that prompted the young US Forest Service (USFS) to create policy to try to prevent and suppress fires.

“In 1935, the USFS established the 10 a.m. rule,” says Josh Hankes, executive director of Routt County Wildfire Mitigation Council (RCWMC). “This directed that every fire should be suppressed by 10 a.m. the day after the initial report. This effectively disrupted the natural ecological cycle that has historically included fire. The result has been thicker, denser forests and an unprecedented buildup of fuels.”

“It took a long time for us to realize fire is good, necessary, and an intrinsic part of how these systems evolved and how many of them regenerate,” — Carolina Manruquez, USFS Lead Forester

The American public became trained to expect wildfire prevention and suppression. In the 1960s and 1970s, however, research was showing the need for fire to once again play a role in forest ecology. This developed into letting naturally caused wildfires burn in wilderness areas without suppression, unless they were threatening people or property.

“Native Americans used fire as a tool for a variety of cultural and management reasons,” Colorado State Forest Service (CSFS) Lead Forester Carolina Manriquez said. “During these earlier eras, there was a lot more fire on the landscape, and a lot more diversity in terms of ages and density of vegetation, and fewer trees overall. Now, natural resource managers are actively engaging with Traditional Ecological Knowledge that has been passed on through generations within Tribal nations, to find a better approach to deal with our current conditions.”

Results of fire suppression

When CSFS is doing an inventory of an area, they look at old burned tree stumps, called fire snags. This tells them when fire was there in the past, and what vegetation has grown back since. There were a lot of fires in our region at the turn of the century, about 130 years ago, but not many fires since then.

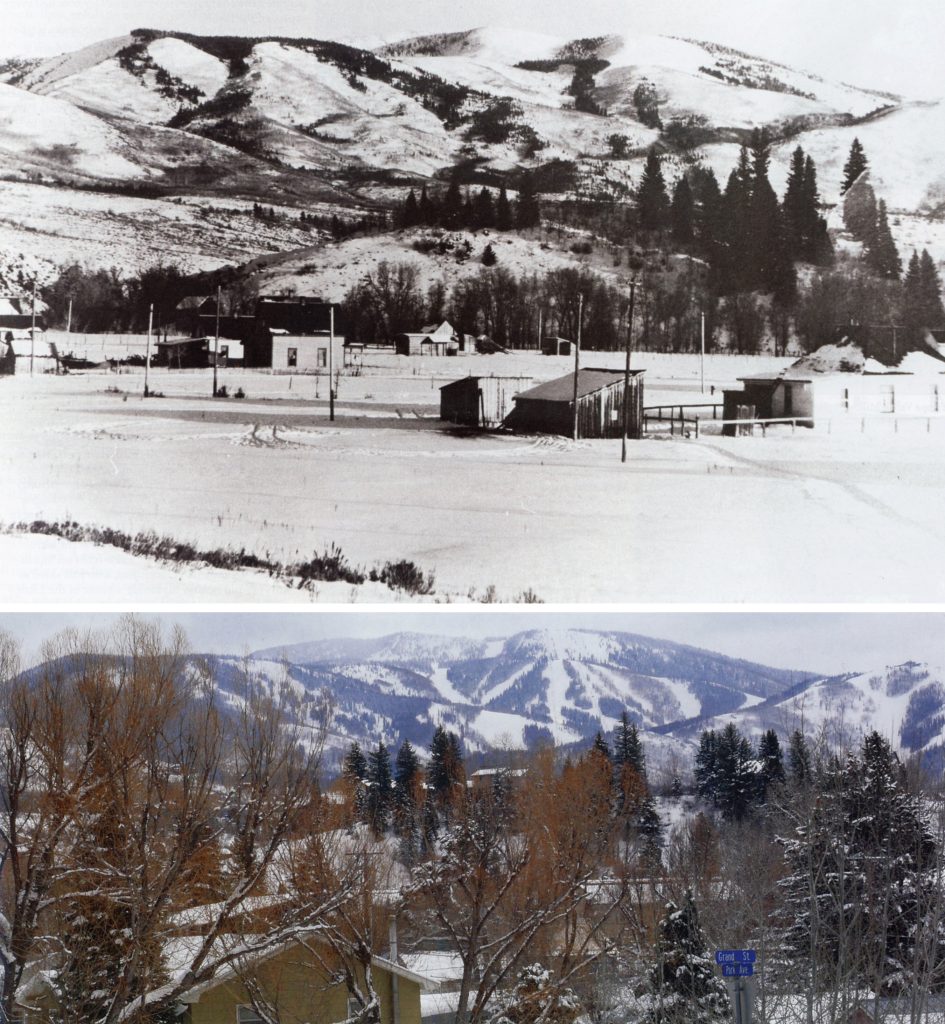

Another way to understand the history of our landscape is to look at old photos.

“If you look at any picture from 100 years ago and today, there will be fewer trees in the historic photo,” said Manriquez.

This is because fire suppression in modern times has resulted in more trees on the landscape.

A side by side photo shows the distinction in tree cover on Mount Werner. Photo Courtesy of Ken Proper and the F.M. Light Collection.

The contrast in density of trees shows up well in these two photos from Then and Now: A History of Steamboat Springs, written by Harriet Freiberger with photos by Ken Proper. Even though there are now ski runs cut into the mountain, there are still many more trees in modern times.

Our country’s past fire suppression policy combined with climate change has contributed to the larger, hotter wildfires becoming the norm in the Western United States.

“When a build up of fuels is paired with our rapidly changing climate —hotter, drier, longer summers, extended periods of drought — along with human development in the wildland urban interface (WUI), you have our current recipe for disaster,” Hankes said.

The WUI is the transition between developed areas and unoccupied land. In this zone, homes or structures are adjacent to, or intermingled with forests and other wild landscapes.

Especially for those living in the WUI, but also for all property owners in the rural West, it is important to protect against fire.

Visit the Routt County Wildfire Mitigation Council website, and read through the detailed CSFS guide, The Home Ignition Zone to learn more.

Reducing risk

In an effort to reduce the risk of an extremely destructive wildfire, forest managers look at ways to handle the dense vegetation that is now common. This is not simple or straightforward.

“Every forest type has a different fire regime,” Manriquez said. “Every forest type grows differently and responds differently to treatment.”

A fire regime is the pattern that fire usually takes in an ecosystem over time. This is determined by studying the frequency, intensity, season, and type of fire common to that area.

Watch Fire Regimes to learn more.

There are management techniques in our region that can help reduce the risk of a large-scale, extremely hot fire.

“These techniques are being employed as best they can with limitations on capacity and resources,” Hankes said. “Prescribed burns, fuels reduction projects, community resilience initiatives, and watershed vulnerability studies with action plans are all underway, in addition to burn scar surveys and replanting.”

The goal of these techniques is to protect communities while increasing the resiliency of forest systems to disturbance, so that even with fire on the landscape, we will still have forested watersheds.

“It took a long time for us to realize fire is good, necessary, and an intrinsic part of how these systems evolved and how many of them regenerate,” Manriquez said. “Right now, most of what we are doing is removing fuels in certain areas, so that we can bring fire back to the landscape at a lower severity. Essentially, removing fuels means fire will burn with less heat or move more quickly.”

Reducing fuels in dense forests is managed differently depending on species and type of forest. The goal is to maintain a healthy forest while keeping fires from becoming extremely hot megafires that can scorch the soils and remove seed sources for future regrowth.

One of the problems with an extensive fire is that it kills the trees that were pulling carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas, from the air. At the same time, the fire releases a significant amount of carbon into the atmosphere. As the dead trees decompose, they continue to release more carbon. This combination is very detrimental to the goal of lowering carbon in the atmosphere to fight climate change.

Read New NASA Study Tallies Carbon Emissions From Massive Canadian Fires to learn more.

However, the benefits of fires that are left to burn, but are smaller scale, less hot, and possibly leave patches of vegetation unburned are many. Some of the benefits of milder fires are: new forest growth, increased variety of vegetation, improved wildlife habitat following regrowth, diminished risk of a large, severe wildfire, and a landscape still left undamaged enough to provide protection from erosion and floods.

Fireweed blooms in a former burn area.

When a wildfire does come through our region, the area is evaluated immediately after the fire, and then in the following years. This is the time to track what is growing back naturally and determine if the area could benefit from having trees planted by hand.

“Due to our changing climate, forests likely won’t grow back in the same way they have for hundreds if not thousands of years,” Hankes said. “Efforts intended to expedite forest regeneration through analysis and replanting are important to stabilize the soil, reduce the risk of flooding, enhance natural carbon sequestration, and inform future efforts.”

Learning about the complexities of wildfire is important for those of us in Colorado and throughout the West.

“We need support and understanding from the public to do the work we do,” said Manriquez. “This work is so much more complicated, urgent, and with unknown elements, than we want to think it is.”

A group of Yampa Valley Climate Crew volunteers plant trees in the Muddy Slide burn scar in June 2023.

You can help forest regeneration by attending one of Yampa Valley Sustainability Council’s many tree planting or regeneration survey volunteer days. For upcoming events, visit yvsc.org/yvsc-events/. To get notifications of upcoming projects, sign up for YVSC’s newsletter.

Jill Bergman, YVSC Creative Climate Communications Associate | 11 October 2024