Fetcher cattle and newborn calves stand in the field April 10. (Photo by Jill Bergman)

The Elk River flows with early April snowmelt and rushes alongside the Fetcher Ranch. Winding down from the Zirkel Wilderness, this 32 mile long river in North Routt County, Colorado is the main source of water for the ranching communities along its length.

Over the span of 75 years, the Fetcher family has come to trust that it will get snow each winter, and runoff filling the Elk River each spring. During the summer, the river holds plenty of water to irrigate hay meadows. This hay is used to feed their cattle during winter months from November to May. Trust in the weather has developed from years of observation and tracking changes, each family member in their own way.

For Jay Fetcher, this includes noting down when the snow melts off one of the family’s hay meadows, a tradition started by his father, John Fetcher, in 1951. John was one of the founders of the Steamboat Ski Area as well as an expert in water storage and planning who was instrumental in creating Steamboat Lake and Stagecoach Reservoir.

- Gael and Jay Fetcher give a tour of their family ranch on April 10, 2024. (Photo by Jill Bergman)

- The Fetcher family on Christmas in 1956. (Courtesy of Fetcher Family)

- The Fetcher Ranch, watercolor by Gael Fetcher

Jay thought his father started tracking the date the meadow ‘bared off’ as a way to stay organized and get busy with spring projects.

“Snowmelt on the field signaled that within a week, these cows will be out on the pasture,” Jay said. “Yesterday, we needed to get all of the fence fixed.”

Understanding the timing of chores was something the Fetchers learned through trial, error, and help from neighbors. The family moved to North Routt and started ranching near Clark and Hahn’s Peak, Colorado when Jay was just two years old in 1949. There weren’t many structures on the ranch at the time, but the barn built by homesteader Henry McPhee in 1905 is still standing. The Fetchers raised cows their first year before they even had corrals. An engineer, John quickly made improvements including fencing, buildings, and irrigation.

“John was a curious person,” said Gael, Jay’s wife, who has also spent decades working on the ranch. “He always had a rain gauge out. He carried around a notebook like a diary, and he’d jot things down.”

Remembering the notebooks, Jay added, “I was going through and trying to pick out significant stuff, and June 3, 1952, I read, ‘cut off Jay’s finger.’ I was 4 years old in the hay meadow and stuck my finger in part of a machine. He took me to the neighbor who drove me down to Mom. Underneath that diary entry is the rest of the work he did that day!”

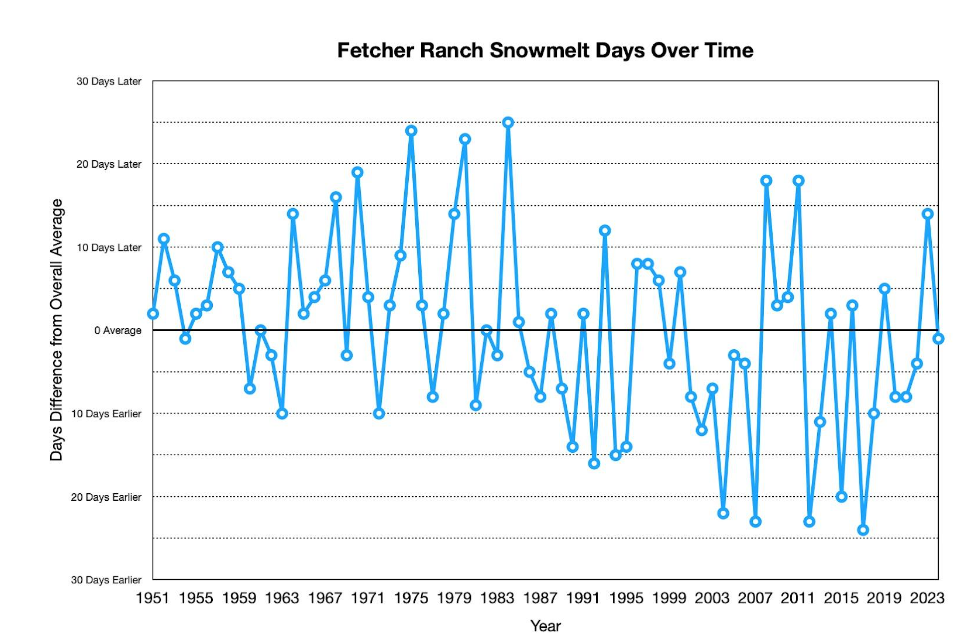

Because he kept John’s notebooks, Jay can compare changes in weather, wildlife, and culture from past to present. The family has seen firsthand the variability of snowmelt from year to year.

These ‘snow off the meadow’ dates have been creeping earlier, which could indicate that our snowpack season is getting shorter. In 2004, the snow melted off the meadow on March 26, the first time a date was recorded in March since 1951. Four more March dates have been recorded since. The Fetcher’s data show that on average, the snow is melting off their meadow 11 days earlier now than it did in the 1950s.

The points on the graph show wide variations during periods, especially since the beginning of this century. This reflects what climate scientists say is happening, more variation in our climate and weather patterns.

A graph demonstrates the fluctuation from the overall average of which day the snow melts off the meadow at the Fetcher Ranch. (Graph by Tom DeMay)

“This increased variability has many impacts like causing more intense and frequent extreme events like droughts, flooding, and heat waves,” said Madison Muxworthy, soil moisture, water & snow program manager with Yampa Valley Sustainability Council. “As an example, climate variability could cause higher temperatures during the irrigation season, causing agricultural producers to irrigate for longer periods and use more water.”

The snow wasn’t the only thing the Fetchers kept track of over the years. They were also watching the wildlife, and noticing when a new species was sighted, or others no longer appeared in the area.

“People take notes on observations in the world around them for different reasons and in different ways. Like John Fetcher, it may be an innate sense of curiosity; like Jay, it may be a way to track seasons and cycles of work; or, like Gael, it may be a way of remembering a scene by painting the season, light, and animals in a place that you love.”

As a child, Jay walked to the small schoolhouse in Clark, the nearby town. “Growing up here, as we walked, we would chase the frogs that were hopping across the road,” he said. “I don’t see frogs or toads here anymore. So, I started thinking about the animals that I grew up with that aren’t here now. Up at Hahn’s Peak Ranch, there were badgers everywhere. They were scary. You’d go out with a dog to irrigate, and a badger would chase the dog.”

Crane Dance, watercolor by Gael Fetcher

Jay has a list of wildlife species that he sees, or no longer sees, and the timing. Elk, moose, bald eagles, and sandhill cranes are thriving in the area now, although he rarely saw them when he was a child.

“I had to catch the horse, and go to check on the cows,” he described. “I went over this rise and saw two critters that looked like deer. They were sandhill cranes. They were the first cranes I ever saw here. That was 1964. Now it’s so much fun, because they are everywhere. The cranes are a real sign of spring.”

Jay graduated from the University of Wyoming with a degree in Animal Science, and later a Master’s Degree in Population Genetics from Colorado State University. He took over the ranch management while still in college.

In the 1970s Gael met Jay on a visit to the ranch with a friend and soon they were married. Gael had artistic talents, but not much time for creativity with a busy work and family life. Later, after they had moved ‘to town’ Gael was able to explore watercolor and devote time to painting. The landscape around their property, birds, and other wildlife are her inspirations.

People take notes on observations in the world around them for different reasons and in different ways. Like John Fetcher, it may be an innate sense of curiosity; like Jay, it may be a way to track seasons and cycles of work; or, like Gael, it may be a way of remembering a scene by painting the season, light, and animals in a place that you love.

As we move through transformations brought by climate change, try taking notes in your own way about what you see around you. You don’t need to be a scientist, but it helps to be consistent. Noting migratory birds along the Yampa River, the first snow each fall, or dates that wildflowers bloom are examples of citizen science, a wonderful way to appreciate the natural world.

To the left of the fence sits the hay meadow that Jay Fetcher watches to note down the date that the snow melts. (Photo by Jill Bergman, April 10, 2024)

To work on group projects, check with Yampa Valley Sustainability Council, Yampatika, Friends of the Yampa, or go online to citizenscience.gov.

This spring at the Fetcher Ranch, the new calves are running around their moms, sandhill cranes have returned, and Jay noticed that the snow melted off the meadow April 16, just a week after the photo above was taken.

24 May 2024

Jill Bergman | YVSC Creative Climate Communications Associate