This article is the second part of the Healthy Forests series. Read Part 1: Along the Yampa River, here and Part 3: The Important of Fire, here.

There are areas around Steamboat Springs that are heavily forested. Even a forest we think of as untouched is the result of management values that have changed over the years. Because of different priorities, forests may be allowed to burn or not, logged or left standing, planted or left to natural regrowth. No matter the human goals, our forests provide countless benefits. The trees capture carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas, and release oxygen. They also prevent erosion, maintain healthy watersheds, and provide habitat for wildlife.

The forests in our area are living through long term drought and warmer temperatures because of climate change. These forests are generally drier and hold many dead trees from beetle kill or disease, making them susceptible to the more intense wildfires occurring in the Western United States in the last few years. Once a severe wildfire has passed, trees struggle to reestablish because the soils have been scorched and seed sources from healthy trees are too far away.

Abby Vander Graaff and Silas Axtell conduct a regeneration survey in Big Red Park in August 2023.

Yampa Valley Sustainability Council (YVSC) has been working in partnership with the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) since 2022 to conduct regeneration surveys on federal lands. These surveys, led by experts, take volunteers to past wildfire sites to determine what is growing back naturally. This provides the observational data needed to decide if an area could use help with tree planting, or if it’s already happening naturally.

Colorado State Forest Service (CSFS), YVSC, and other organizations are trying to regenerate forests in key watersheds where they are needed to stabilize the landscape and keep the water flowing and filtrated.

“There is a sense of urgency that we need to carry out restoration work in the next 5 to 10 years to really make a difference,” said CSFS Lead Forester Carolina Manriquez. “Mother Nature can do this and take as much time as she needs for trees to grow back. It might take 500 years naturally, but we can’t wait that long.”

“Climate change is disrupting our systems,” Manriquez said. “Even 10 years ago, we used to see abundant regeneration after a timber harvest, thousands of trees per acre coming back naturally into the forest. We’re not seeing that level of regeneration happen in certain places now, so we have to adapt our practices.”

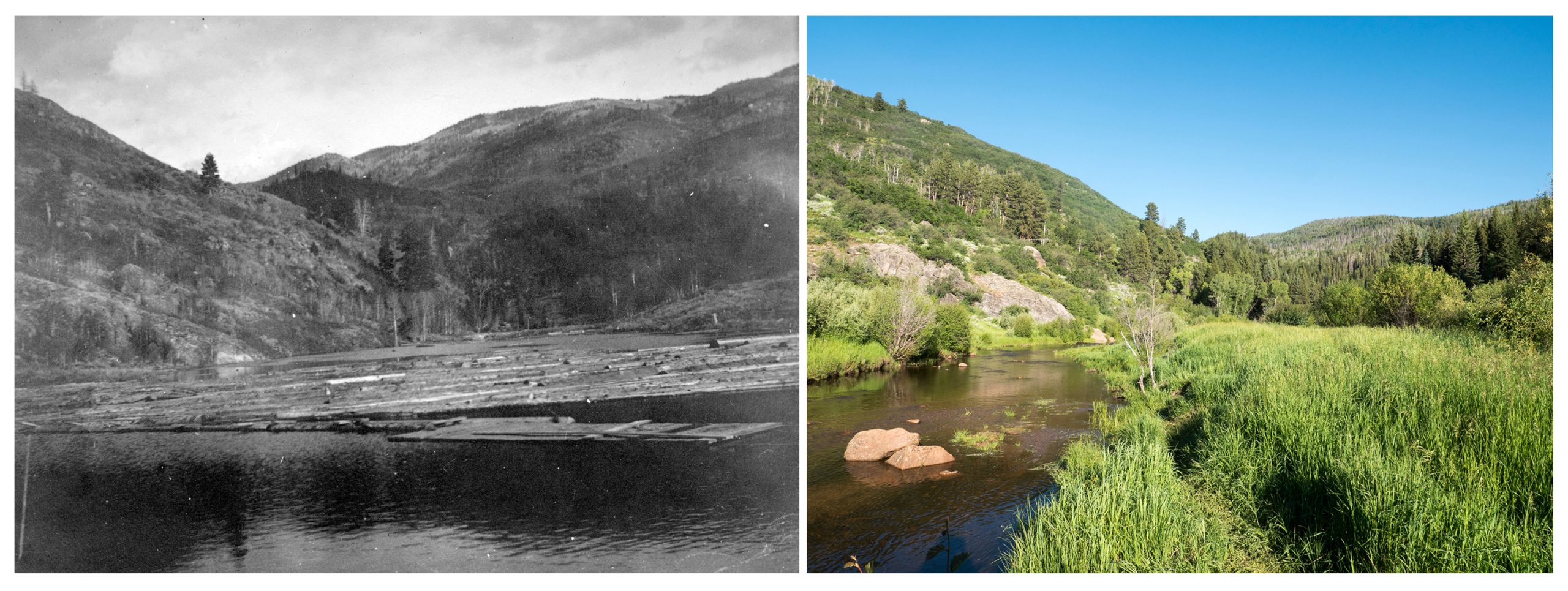

A side by side photo shows Sarvis Creek Lumber Company in 1914 (left, courtesy of Tread of Pioneers Museum) and Sarvis Creek in 2023 (right, courtesy of Ken Proper).

An example of past regeneration was uncovered by photographer and author Ken Proper. In research for an upcoming book about the Yampa River watershed, he is comparing past and current landscape photos in the region. This is a technique CSFS also uses. The Sarvis Creek Lumber Company clear cut timber in that drainage in 1919, but the modern photo shows the hillsides reforested. To achieve the same growth in areas now, people may need to help by planting trees.

“In order to prevent serious erosion and landscape conversion into grasslands, it is our responsibility to plant seedlings and spread seeds in these severely burned areas that are not regenerating naturally,” YVSC Forest Resilience Projects Manager Dakota Dolan said. “We are speeding up the process and guaranteeing future forests where they are otherwise not promised.”

Talking Green: What are regeneration surveys and why do they matter in forest recovery post-fire?

Changing Climate, Changing Habitat

We are used to thinking about wildlife migrating, but plants, including trees, also move by reproducing into new areas. A species will shift its range through a variety of different processes including planting by people. If new growth takes hold in an area, it’s because it is well suited to the climate there. Each species has a preference for elevation, temperature, and water availability.

CSFS is planting trees they think will be best adapted to an area in the near future. The tree line, or limit at which trees survive, is going to go up in elevation because of climate change, and there will likely be less water, Manriquez predicts.

To learn more about identifying trees, visit the CSFS webpage.

Spruce trees need more water than pine, so spruce may struggle to survive in a drier climate. Lodgepole pines also grow more quickly than spruce and could mature at 60 or 70 years old. Douglas fir and Engelmann spruce live to be hundreds of years old, taking longer than lodgepole pine or subalpine fir to mature.

Manriquez has noticed that the oak brush on the mountains surrounding Steamboat Springs have moved up in elevation a little bit. Shrubs are moving more quickly than trees. Their berries get eaten by wildlife and the seeds deposited in droppings, or other seeds may stick to fur and travel.

A lodgepole pine planted in the Muddy Slide burn area.

When a species of tree has died in an area because of disease or fire, another species may migrate into the spot. For example, there are areas of fir decline, possibly because of drought, but aspen are taking over those areas. Aspen trees are better suited to living with less water and potential fire. After fire, aspen seedlings have also been noticed to move up in elevation, higher than previously seen.

“We’re trying to do both the studies and the planting that we think will benefit the forest,” Manriquez said. “In 50 years time, what’s going to be growing here based on the climate models and hydrology of the place? We are hoping to set up the studies and do the management that can provide guidance to the future forest managers and conservationists.”

YVSC is taking volunteers out to conduct regeneration surveys in the Big Red Park and Silver Creek burn scars on Thursdays throughout the fall. To learn more or sign up, email Dakota Dolan at dakota@yvsc.org.

You can also learn more about Yampa Valley forest resilience on YVSC’s website. For more volunteer opportunities check out the upcoming events calendar.

Jill Bergman, YVSC Creative Climate Communications Associate | 25 September 2024